We steered a spacecraft into an asteroid

From seeing further into space than ever before to viewing our neighbouring planets in brand new detail, it’s safe to say more of us are talking about the skies above than in previous years.

Now, NASA has made headlines for crashing a spacecraft into a distant asteroid in a historic first for humanity.

After leaving Earth last November, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spaceship travelled at a speedy 23,500 kilometres per hour for ten months to reach its target, an asteroid moonlet called Dimorphos.

Dimorphos is a relatively small asteroid with a diameter of 160 metres - about the same size as the Great Pyramid of Giza - that orbits Didymos, a larger asteroid boasting a diameter of 780 metres.

DART, meanwhile, is approximately the size of a refrigerator - but size isn’t everything.

The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft is dwarfed by its target, Dimorphos, as well as Didymos, which Dimorphos orbits. Image: NASA / John Hopkins APL

Located 11.2 million kilometres away from us, Dimorphus might not pose any risk to Earth, but it did serve as a suitable target for NASA to test whether a head-on collision from DART could cause the asteroid to change its orbit.

This experiment, which uses a technique called kinetic impact to change the asteroid’s orbit, could determine whether it’s possible to prevent asteroids and other cosmic objects from colliding with Earth and avoid the devastating aftereffects of such a collision.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson explained that the experiment is part of the organisation’s overall planetary defence strategy.

“At its core, DART represents an unprecedented success for planetary defence, but it is also a mission of unity with a real benefit for all humanity,” he said.

“As NASA studies the cosmos and our home planet, we’re also working to protect that home, and this international collaboration turned science fiction into science fact, demonstrating one way to protect Earth.”

Rebecca Allen, an astronomer at Swinburne University of Technology told the ABC that everything from the location of the impact, how fast DART travelled, and even its size are factors that could affect Dimorphos’ orbit.

"This vending-sized machine spacecraft, will it have enough kinetic impact to drastically or really measurably change the orbit of this asteroid? That's what we're trying to learn,” she added.

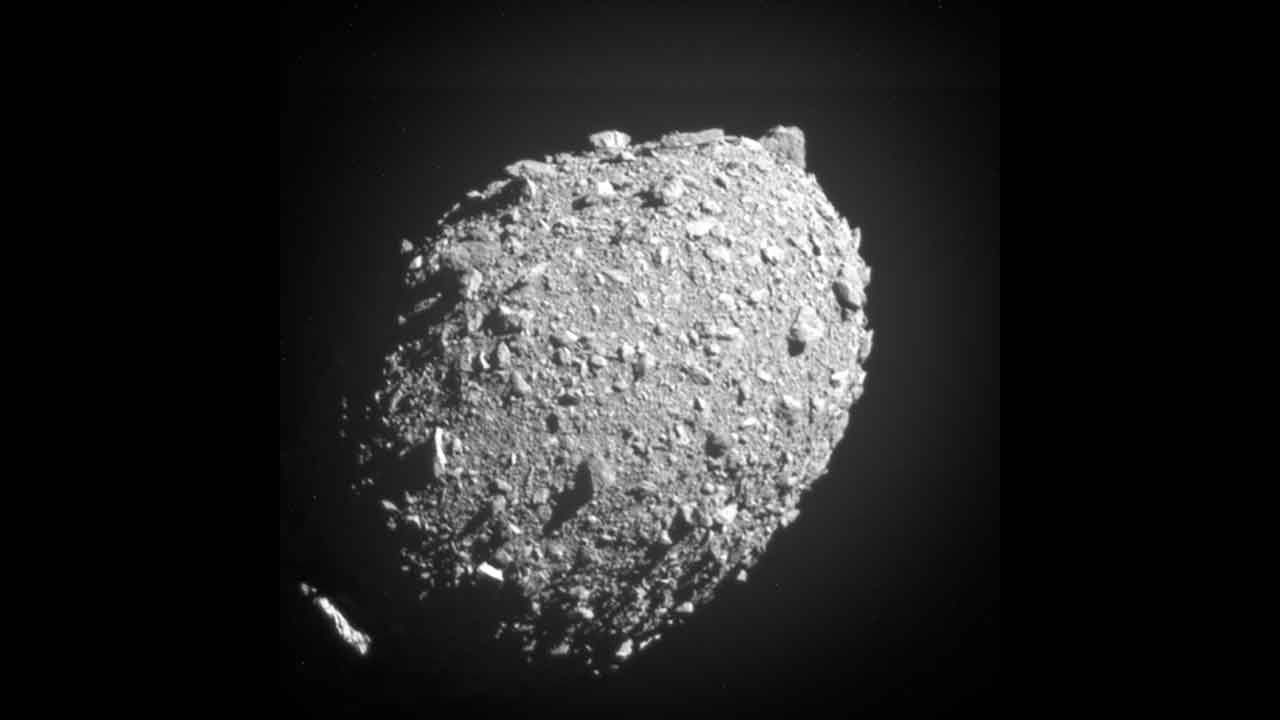

Shots taken from DART’s onboard camera showed asteroids Dimorphos and Didymos (left), and an up-close look at Dimorphos before DART crashed (right). Images: NASA / John Hopkins APL

What happens now?

Though DART successfully collided with Dimorphus on Tuesday morning (NZDT), we won’t know whether the collision actually resulted in a change in orbit.

It will take anywhere from several days to weeks to determine whether it worked, and we can expect to learn more over the coming months.

“Over the next two months we’re going to see more information from the investigation team on what what period change did we actually make,” Dr Elena Adams, a DART Mission Systems Engineer, said.

“That’s our number two goal, number one was hit the asteroid, which we’ve done but now number two is really measure that period change and characterise how much we actually put out.”

In a statement, NASA said researchers are expecting the path Dimorphos takes around Didymos to shorten by just one percent, or about 10 minutes.

But even this seemingly tiny change can have an impact over time, experts stress.

"Just a small change in its speed is all we need to make a significant difference in the path an asteroid travels.” said Dr Thomas Zurbuchen, an associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA’s Washington headquarters.

The next few months will also see NASA use telescopes positioned on Earth and in space to observe the outcome of the collision, including measuring changes to Dimorphos’ orbit.

Images will also be taken by LICIACube (Light Italian Cubesat for Imaging Asteroids), which deployed from DART fifteen days before the impact, with the European Space Agency’s Hera project scheduled to conduct surveys of Dimorphos and Didymos - with a focus on the crater created by the collision - in 2026.

The images will add to the collection of photos taken by DRACO (Didymos Reconnaissance Camera for Optical navigation), which was onboard DART when it crashed.

As well as shots showing Didymos and Dimorphos, the images depict the rocky terrain of Dimorphos’ surface up close.

DART’s onboard camera, DRACO, captured the final moments before the spacecraft crashed into the surface of Dimorphos. Images: NASA / John Hopkins APL

The last photo, taken about one second before impact, was being transmitted to Earth when the craft crashed, resulting in a partial picture.

“DART’s success provides a significant addition to the essential toolbox we must have to protect Earth from a devastating impact by an asteroid,” said Lindley Johnson, NASA’s Planetary Defense Officer.

“This demonstrates we are no longer powerless to prevent this type of natural disaster.”

Image: NASA / John Hopkins APL